THE HOME GUARD

OF GREAT BRITAIN WEBSITE - MISCELLANEOUS INFORMATION PAGES

DEVON MEMORIES

KEYNEDON MILL

and THE EVACUEES

AUGUST 1941

by Chris Myers

April 2025

|

This and

associated pages are hosted by the staffshomeguard

website (whose subject is the Home Guard of Great

Britain, 1940-44). They bring together various

memories, all recalled by the author in old age, of a childhood in

Streetly, Staffordshire (as it was then

called) and life in it during the period 1936-1961;

and of holidays in

Devon

during the same period.

This page contains:

BACKGROUND NOTE (1939-1941)

KEYNEDON MILL AND THE

EVACUEES (1941)

|

BACKGROUND

NOTE (1939-1941)

Birmingham, or at least its

inner-city areas, suffered

grievously under the

Luftwaffe bomber attacks of

the Birmingham Blitz which

lasted mainly from the

autumn of 1940, through the

winter and into the spring

of 1941.

Many

children from that city -

and of course from other

industrialised areas across

the country - were evacuated

at the outbreak of war in

September 1939 to places

where the risk of future

attack was much reduced.

This image, which appeared

in a Birmingham newspaper on

2nd September 1939, shows a

few of them, boarding a

train at Snow Hill Station

in the city. When the

predicted aerial onslaught

did not happen, many drifted

back home until, almost

exactly a year after the

first, by which time the

dangers of life in those

areas had become all too

clear,

a second evacuation took

place in September 1940. Many

children from that city -

and of course from other

industrialised areas across

the country - were evacuated

at the outbreak of war in

September 1939 to places

where the risk of future

attack was much reduced.

This image, which appeared

in a Birmingham newspaper on

2nd September 1939, shows a

few of them, boarding a

train at Snow Hill Station

in the city. When the

predicted aerial onslaught

did not happen, many drifted

back home until, almost

exactly a year after the

first, by which time the

dangers of life in those

areas had become all too

clear,

a second evacuation took

place in September 1940.

As for me personally, we lived on the

north-eastern fringe of the

city, away from the more

industrialised and densely

populated areas which were

most at risk, and so I was

not part of the 1939 or 1940

evacuations of children from

Birmingham. (In fact I had

never even heard of the term

"evacuees" until the summer

of 1941 when I was

five-and-a-bit and in South

Devon where I learnt exactly

what it meant). There was

some consideration given to

an offer from an American

friend of my father of a

U.S. home "for the duration"

for my sister and me, in

order to escape not only the

bombing but a possible

invasion and occupation; but

my parents eventually

declined it - perhaps the

risks of a Transatlantic

crossing or the pain of

separation loomed too large

for them - and the decision

was that we should stick it

out together, for better or

for worse. I as a

four-year-old of course knew

nothing of these

deliberations.

KEYNEDON MILL AND THE

EVACUEES (1941)

By the summer of 1941 Hitler’s attentions were

focused firmly to the East

and we were no longer alone,

and intensive aerial bombardment

of the country and the risk

of invasion had both

reduced, at least

temporarily. So my father

decided that it was time

that we should all try

to get a holiday. (Leisure

motoring was still permitted

even though petrol was

severely rationed: within a

short time all non-essential

car use would be banned

totally). The choice of venue

was obvious: since the

mid-1930s, and before I was

born, the family had stayed

every summer at a farm in

the South Hams of

Devonshire, an area at that

time

sleepy and little changed in

the previous hundred years.

For obvious reasons we had

not been there in the

previous summer of 1940:

then, everyone was in daily

fear of invasion and the

German Dorniers and Heinkels

and Junkers were overhead

somewhere every day and,

later, every night. Most young men were awaiting

call-up or had already

disappeared and everyone was

expected,

one way or the other, to be contributing to

the war effort. In our house

my father, supported by my

seventeen-year-old elder

brother, was spending all

his non-working hours on

local Home Guard duties -

nightly patrols and

observation, exercises, guarding

vulnerable points, and, in his case, constant

training to make his platoon

an effective infantry unit.

My mother volunteered for

the W.V.S. and continued to

care for the family. It was not a time

for holidays.

But now, a year later and

shortly after German troops

poured into Russia, Dad

counted his petrol coupons

and made the decision.

The house was

Keneydon Mill, located

between the villages of

Frogmore and Sherford. Here

it is with my mother

greeting us from an upper

window while my elder

brother stands at the gate;

it's probably summer 1936 or

1937.

So off there the

four of us went in our black

Ford Prefect, my parents, my

elder sister and I for the

nine or ten hour journey.

My brother Graham stayed at

home because of work and

Home Guard duties.

(This

was only the second major

journey the car had made

since its purchase in early

1940, and it would be the

last for four years. The

first had been a week-end in

Blackpool in May 1940 - not

the best timing for the

family as that moment marked

the end of the "Phoney War"

and the beginning of the

real one. Hitler was

attacking Holland, Belgium and

France and we cut short

our little holiday, loaded

up and drove off out of

Blackpool towards the safety

of home). (This

was only the second major

journey the car had made

since its purchase in early

1940, and it would be the

last for four years. The

first had been a week-end in

Blackpool in May 1940 - not

the best timing for the

family as that moment marked

the end of the "Phoney War"

and the beginning of the

real one. Hitler was

attacking Holland, Belgium and

France and we cut short

our little holiday, loaded

up and drove off out of

Blackpool towards the safety

of home).

After delivering us

at Keynedon,

Dad did not linger long with

us there and I

remember sadly waving him off from

the bridge at Frogmore as he

set off on his day-long,

lonely journey back to a

battered city, work and

worry in an industry working

flat-out to supply the war

effort, tight food rationing

and all his Home Guard

duties. We then trudged back

down the lane to the

farmhouse, the three of us, and continued our

holiday.

Some time later, a week or

ten days perhaps, Dad

rejoined us having travelled

by rail, now with Graham, as

they abandoned their work

and Home Guard

responsibilities for a short

while in favour of the

attractions of a few days of

badly needed rest, fresh air

and largely unrationed food.

As a five-year-old I recall

their exhausted arrival late

at night in the farm's

hallway as they stood

blinking in the lamplight

after their walk with

luggage in the dark from

Kingsbridge Station all the

way to Keynedon Mill, near

Sherford.

How lucky we all were to

have a holiday at that time!

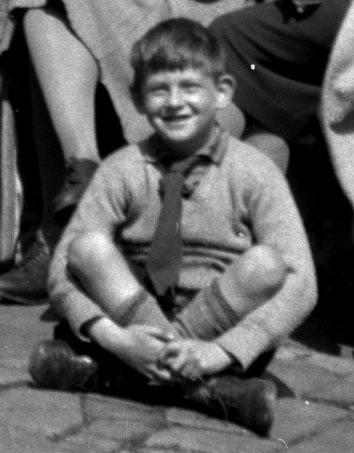

We were not the only guests

at Keynedon Mill on this

visit. There were three boys

there too, unexpectedly. But

they were not exactly on

holiday like us. They were

something called evacuees.

And they were brothers. Bob

was probably a year or so

older than I; he had an

elder brother of 10 or 11

whose name I can’t remember

and so I shall call him

Billy; and the head of this

family was the eldest, named

I think Frank, a remote,

grown-up fellow of 15 or 16

whom one saw only rarely. I

was told that they came from

a part of Birmingham called

Ladywood and had been sent

there to avoid the bombing. I

hadn’t heard of that place

before but I was struck by

what a nice name it was and

had visions of dense foliage

and grassy, sunlit clearings

occupied by ladies in pretty

dresses having a picnic.

(Anyone who knew that part

of inner-city Birmingham

then would have realised

that this vision of the area was

somewhat less than

accurate).

The boys lived in a large,

white-washed single room at

Keynedon, the loft either of

the main house or of one of

the outbuildings. They ate

with the farmer’s family, at

a large table in a room to

the right of the entrance

hall of the farmhouse. I

still have a vision of them

sitting there as we passed

through to our own room. The

meal was presided over by

the commanding presence of

Mrs. Cumming, a lady of

great antiquity - possibly

in her early fifties - and

with a frightening cane

lying ready to hand; this

was of sufficient length to

reach the younger boys

seated further down the

table in case they required

any guidance.

I imagine that Bob and Billy

attended the local school in

the nearby tiny village of

Sherford but it was August

and so they were on holiday.

Frank on the other hand

seemed to be engaged the

whole time on farm duties

and I know that he got up at

some ungodly hour every

morning to fetch the cattle

for milking. I didn’t see

much of Billy and can’t say

whether he had his own list

of duties but I played a lot

with Bob who seemed to have

plenty of freedom.

In later years I have often

pondered on the mystery of

how those three lads ended

up in such a remote spot, so

far from home. I don’t know

whether they were part of

the September 1939

evacuation although they

probably were, since at that

stage the risk of invasion

was something quite inconceivable

to everyone - including those

organising this huge

movement of children and

others - and so the south

coast must have been

regarded as an acceptable

destination. It seems

strange, nevertheless, that they were sent

such a long way from home

from where their parents,

assuming they had any,

would have found it almost

impossible to visit them.

And when the threat of

invasion loomed out of

nowhere from the

middle of 1940, lodgings

only a mile or two from the

South Coast, even so far

west, would not have

appeared to be

to be the safest of

locations. Perhaps other

factors affected the

decision.

I can imagine them being

shepherded on to a train at

Snow Hill Station in

Birmingham, labeled and

carrying a small package of

their possessions and of

course their gas mask, as

they embarked on the

day-long journey into the

complete unknown with the

help of the Great Western

Railway. Memoirs of children

in this situation, some of

whom had never been out of

their cities or on a train

before, speak of the wonders

of the journey. And so I

imagine our trio, gazing out

of the window at an

ever-changing tableau of

meadow and woodland,

cornfields and unfamiliar

farm animals as they

trundled south. In their

compartment excitement and

wonder at the unfamiliar

sights must have been

intense but later, as the

day progressed and tiredness

started to overcome them,

that would have been

replaced by apprehension and

even fear about what faced

them. They would have passed

through Bristol and Exeter,

perhaps changing trains,

perhaps seeing, every now

and again, many of their

companions leaving the train

at intermediate stops.

Finally they would have

alighted at Brent Station,

just like these evacuees

from Bristol, on their way

to Kingsbridge and new homes

in the surrounding area.

(This image, and others

associated with it, are held

in the Imperial War Museum

Archive and depict the

journey of a group of

Bristol children being

evacuated in February 1941

to new homes in the

Kingsbridge area).

At Brent our

trio would have

clambered aboard a little

two-coach train for the last

leg of their long journey. A

diminutive GWR tank engine

would have hauled them down

the branch-line through the

rolling countryside of

pasture and cornfield and red Devonshire

earth, where the hedgerows

and line-side trees would

have seemed close enough to

lean out and touch. They

would have stopped at

Avonwick, Gara Bridge and

Loddiswell - did any of

their companions get off

there? - and after about

thirty minutes they would have reached

their destination, and the

very last station,

Kingsbridge. (I have

memories of that branch-line

journey myself, from other

times). What an

alien world it must have

seemed as they got down off

the train and looked around

them in the quiet of

evening, at milk churns and

empty cattle pens and an

almost deserted station, the

end of a line which

stretched all the way back

to the bustle and soot of

Snow Hill and the middle of

Birmingham. And yet

.jpg) they

still had another five or

six miles to go in the

gathering dusk - now perhaps

by bus and on foot, or

possibly by horse and cart -

on through small villages

and past scattered houses, finally turning off the

road at Frogmore down a lane

just wide enough to allow

their passing. they

still had another five or

six miles to go in the

gathering dusk - now perhaps

by bus and on foot, or

possibly by horse and cart -

on through small villages

and past scattered houses, finally turning off the

road at Frogmore down a lane

just wide enough to allow

their passing.

And

as they approached the farm, perhaps

they even saw Mrs.

Cumming standing at the

gate to greet

their arrival.

Nor do I know how long they

stopped at Keynedon. Early

in 1944 the farm and the

surrounding area was itself

evacuated at short notice

when the US Army took over

the nearby stretch of coast

and adjacent countryside as

a training ground for the

D-Day landings which were to

come six months later. The

Cumming family moved with

all their livestock into

tiny premises in Frogmore.

They were still there in

August 1945 when we visited

them. But the boys weren’t

and of course I wasn’t

interested enough to ask

after them. I have often

wondered - and still do as I

write this - what happened to

them and how much their time

in Devon, with all its fresh

air and healthy food but

remoteness from loved ones

and familiar city

surroundings, influenced their

later life. And just how

that clash of totally

different cultures, inner

city industrial Birmingham

and remote, agricultural

Devon, worked, day in, day

out.

My friendship with Bob came

to an abrupt and unhappy

end. The facilities in the

farmhouse were basic in the

extreme: candles and oil

lamps; an outside pump for

water and, inside, ewers,

jugs and

china gesunders in place of

any plumbing; and the main -

or so it seemed - lavatory a

fruity, fly-blown, wooden

structure containing an

earth closet and sheets of

newspaper. The latter

"convenience" was, hardly

conveniently, located out of

the front door, along the

lane a few yards, up some

steps cut into the earth

bank and across a short

stretch of grass to near the

waterwheel - itself a dark

and forbidding structure,

now unused and resting

stationary in a large,

threatening strip of dark

water, far below. I was

strictly prohibited from

going anywhere near the

latter because of the

obvious dangers of falling

over the edge; and, equally,

from approaching, let alone

entering, the wooden closet.

There the threat was more

mysterious, more veiled,

"Diphtheria” being muttered

as it always was when

anything vaguely unhealthy

was being discussed. Bob and

I were playing near the

waterwheel one day, feeding

ducks with white berries

plucked from a nearby bush.

Getting bored with this,

although the ducks weren’t,

we decided to investigate

the little house. And not

only that, but to leave our

visiting card there too. All

of this was of course great

fun. But somehow or other

the incident came to the

notice of my parents and,

probably with a bit of

assistance from me in the

uproar which followed, Bob got

the blame for initiating

this dreadful crime. It must have

been decided that he was not

a suitable companion for me

and I never played with him

again. Nor after our

departure only a few days later

ever heard anything further

about him.

I never even knew Bob's

family name. I hope that he

had a good life and that he

always remembered, as I

still do, a sunny day in the

South Hams of Devon some 84

years ago, a flock of greedy

white ducks and a smelly old

hut on the edge of a meadow

by a waterwheel. And a

friendly playmate to enjoy

it all with.

**********

|

FOOTNOTE

- April 2025

How good it would be to

identify this young group,

so far from their home and

family and friends!

What were their

circumstances in that

inner area of a vast,

industrialised city? And how

did their lives work out

there, after their return

home? Modern methods of

research would probably tell

us - but not without

knowledge of their surname

and perhaps exact

home location.......and could any

local Devon history records,

such as Sherford School

pupil lists

- or any personal local knowledge - ever

provide us with that?

**********

Further information about

that 1941 holiday at

Keynedon Mill, and about

previous holidays there, can be seen in

an associated article:

KEYNEDON MILL and THE

CUMMING FAMILY - 1935-39,

1941

And of the way to

Keynedon:

FROM FROGMORE TO KEYNEDON -

1937 |

**********

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Please see INDEX page for

general acknowledgements.

Additionally, grateful

acknowledgement is made to

the unknown online source of

the Birmingham newspaper

cutting, and to IWM for the

Brent image. |

This

family and local history page is

hosted by

www.staffshomeguard.co.uk

(The Home Guard of Great Britain,

1940-1944)

All

text and images are, unless

otherwise stated, © The Myers Family

2024 &

INDEX

Home Guard of

Great Britain

website

1940-44 |

|

INDEX

Streetly and Family

Memories

1936-61

|

INDEX

Devon Memories

1936-61

|

L9E (previously L8A16, September

2024, updated April 2025)

© The

Myers Family 2024

| |